Evaluating Combinations

One of our goals in this chapter is to isolate issues about thinking procedurally. As a case in point, let us consider that, in evaluating combinations, the interpreter is itself following a function.

- To evaluate a combination, do the following:

- Evaluate the subexpressions of the combination.

- Apply the function that is the value of the leftmost subexpression (the operator) to the arguments that are the values of the other subexpressions (the operands).

Even this simple rule illustrates some important points about processes in general. First, observe that the first step dictates that in order to accomplish the evaluation process for a combination we must first perform the evaluation process on each element of the combination. Thus, the evaluation rule is recursive in nature; that is, it includes, as one of its steps, the need to invoke the rule itself.1

Notice how succinctly the idea of recursion can be used to express what, in the case of a deeply nested combination, would otherwise be viewed as a rather complicated process. For example, evaluating

(* (+ 2 (* 4 6))

(+ 3 5 7))

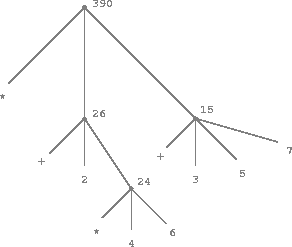

requires that the evaluation rule be applied to four different combinations. We can obtain a picture of this process by representing the combination in the form of a tree, as shown in figure 1.1. Each combination is represented by a node with branches corresponding to the operator and the operands of the combination stemming from it. The terminal nodes (that is, nodes with no branches stemming from them) represent either operators or numbers. Viewing evaluation in terms of the tree, we can imagine that the values of the operands percolate upward, starting from the terminal nodes and then combining at higher and higher levels. In general, we shall see that recursion is a very powerful technique for dealing with hierarchical, treelike objects. In fact, the "percolate values upward" form of the evaluation rule is an example of a general kind of process known as tree accumulation.

Figure 1.1: Tree representation, showing the value of each subcombination.

Next, observe that the repeated application of the first step brings us to the point where we need to evaluate, not combinations, but primitive expressions such as numerals, built-in operators, or other names. We take care of the primitive cases by stipulating that

- the values of numerals are the numbers that they name,

- the values of built-in operators are the machine instruction sequences that carry out the corresponding operations, and

- the values of other names are the objects associated with those names in the environment.

We may regard the second rule as a special case of the third one by stipulating that symbols such as + and * are also included in the global environment, and are associated with the sequences of machine instructions that are their "values." The key point to notice is the role of the environment in determining the meaning of the symbols in expressions. In an interactive language such as Lisp, it is meaningless to speak of the value of an expression such as (+ x 1) without specifying any information about the environment that would provide a meaning for the symbol x (or even for the symbol +). As we shall see in chapter 11, the general notion of the environment as providing a context in which evaluation takes place will play an important role in our understanding of program execution.

Notice that the evaluation rule given above does not handle definitions. For instance, evaluating (set x 3) does not apply set to two arguments, one of which is the value of the symbol x and the other of which is 3, since the purpose of the set is precisely to associate x with a value. (That is, (set x 3) is not a combination.)

Such exceptions to the general evaluation rule are called special forms. set, defun, and define-function are the only examples of a special form that we have seen so far, but we will meet others shortly. Each special form has its own evaluation rule. The various kinds of expressions (each with its associated evaluation rule) constitute the syntax of the programming language. In comparison with most other programming languages, Lisp has a very simple syntax; that is, the evaluation rule for expressions can be described by a simple general rule together with specialized rules for a small number of special forms.2

It may seem strange that the evaluation rule says, as part of the first step, that we should evaluate the leftmost element of a combination, since at this point that can only be an operator such as + or * representing a built-in primitive function such as addition or multiplication. We will see later that it is useful to be able to work with combinations whose operators are themselves compound expressions.

Special syntactic forms that are simply convenient alternative surface structures for things that can be written in more uniform ways are sometimes called syntactic sugar, to use a phrase coined by Peter Landin. In comparison with users of other languages, Lisp programmers, as a rule, are less concerned with matters of syntax. (By contrast, examine any Pascal manual and notice how much of it is devoted to descriptions of syntax.) This disdain for syntax is due partly to the flexibility of Lisp, which makes it easy to change surface syntax, and partly to the observation that many "convenient" syntactic constructs, which make the language less uniform, end up causing more trouble than they are worth when programs become large and complex. In the words of Alan Perlis, "Syntactic sugar causes cancer of the semicolon."